H.R. Giger's nightmare realm

Aliens and cyborgs and mutants, oh my!

Death of a surrealist

In May 2014, news broke that science-fiction surrealist Hans Rudi (H.R.) Giger had passed away. Not everyone recognised this name, but those who did felt a keen loss. Commemorations blazed across the art world, with people as diverse as curators, filmmakers and comic book writers mourning his death.

Some of the fan art produced in this time depicts Giger as a kind of dark genius or netherworld wizard, his body disintegrating as the freakish beings of his career slither out to embrace him. It was as if Giger's fatal fall had only been an illusion, that instead of dying he had finally become part of the nightmarish dimension often glimpsed in his art.

Giger's art resonates with everyone who loves surrealism, horror and cyberpunk. Just as the names David Lynch and H.P. Lovecraft conjure images as vivid and startling as a sucker-punch, Giger's paintings have haunted the consciousness of popular culture for almost four decades.

The biomechanical

His aesthetic is completely singular, usually referred to as the 'biomechanical'. A puzzle of alien beings and shifting landscapes, Giger's art melds the sterile sheen of technology with an organic, almost pulsating fleshiness. Many initially dismissed his paintings as perverse, but he soon gained a cult following and even experienced a lick of mainstream success.

For a lot of people, Giger's name will immediately bring to mind the Alien franchise and the concept art he produced for Ridley Scott's skin-chilling film in 1978. Indeed, if it wasn't for Giger, the film we know wouldn't exist.

This is an impressive legacy in itself, but there is so much more to experience, from Giger's book Necronomicon and portraits of doomed lover Li, to his work on the derailed cyberpunk thriller Dune and assorted album art.

It's in this space that Giger becomes immortal. The body may have perished, but the spirit lives on. To celebrate Giger, techradar has compiled a gallery of his grandest and most unsettling works.

Step into the shadows with us.

- techradar's Movie Week is our celebration of the art of cinema, and the technology that makes it all possible

Nuclear Kids, 1967

Like many artists, the genesis of Giger's artwork can be traced back to childhood.

Born to Swiss parents during the Second World War, his earliest memories were of bluish-black lamps that cast shadows across his house and of looking up at the sky for falling bombs. He heard whispers of atomic warfare, and he was introduced to the concept of organised genocide at a very young age.

Giger's waking world may have been laced with fear, but his dreams were worse. He often suffered from debilitating nightmares, where the everyday trials of living in wartime were amplified and exaggerated.

These nightmares, combined with Giger's burgeoning love for the writings of Samuel Beckett, Lovecraft and Edgar Wright, pushed him into drawing.

In an interview Giger once said: "I draw some of the things I have dreamt. For example, there's a rather unpleasant dream where I am stuck in a tomb and the only way out is a very narrow passage. There are huge stones and I am totally stuck. I cannot move at all. So terrifying, claustrophobic nightmares."

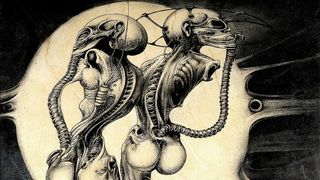

Nuclear Kids is an early Giger painting, but it still features all the characteristics of his famed work.

Two skeletal figures emerge in a minimalist, checkerboard landscape reminiscent of Salvador Dali. A moon, or perhaps another planet, bursts in the sky. It's quite beautiful, with its svelte black and white strokes, but Giger's combination of the erotic and grotesque can also be jarring.

At first, the central bodies look like dancers standing en pointe, until you notice that their long, elegant calves extend into claws, that the rounded buttocks cascade into a web of exposed muscle, and that there are empty sockets where their arms should be. Their faces are a mix of gas mask and skull.

Like much of Giger's work, death and decay become one with sex. It's hard to tell whether Nuclear Kids depicts a ravaged Earth, with humans in the midst of metamorphoses, or if it's another planet inhabited by an entirely different species. The joy of Giger is that we're always guessing.

Birth Machine, 1968

From 1962, Giger attended the School of Commercial Art in Zurich, where he studied architecture and industrial design. This career path may have influenced his chilly biomechanical style, with its emphasis on creative but technical skill. Indeed, Giger's famous landscapes often look like architectural blueprints for an alien planet, full of formidable structures and labyrinthine interiors.

By 1964, Giger was producing his first paintings, usually with a mix of acrylic and Indian ink on photograph paper. He held his first exhibition in 1966 and printed his first poster collection in 1969.

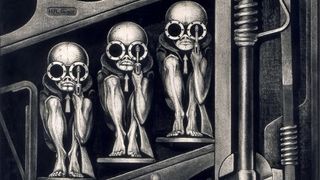

In the ghostly Birth Machine from 1968, Giger further juxtaposes sex and death, as he transforms the womb into the chamber of a pistol. Identical embryos are lined up like cartridges, waiting their turn to be ejected. Instead of miniature humans, the embryos look like machines, flawless little metal men outfitted with goggles and guns. Their expressions are resolute, their destiny accepted.

There are many ways to interpret Birth Machine, none of which Giger has confirmed. Does it reveal a subconscious fear of conception and birth? Perhaps. The birthing process would become a horror show in Alien, for example, when the newborn Xenomorph bursts out of Kane's chest and kills him.

By giving birth to an apex predator, a creature that can only survive by killing its mother, the womb becomes a weapon, and the joys of motherhood are deconstructed and deformed. Instead of giving life and ensuring the future of the human race, the new mother can only promise death.

Conversely, Birth Machine could be a commentary on war. After growing up in the 1940s, Giger had firsthand experience of seeing young men plumped-up on propaganda, just to meet their deaths in combat. Birth Machine could anticipate a future were children are groomed by the state to become perfect soldiers, an assembly line of machines engineered for slaughter.

It's a frightening, dystopian vision where the boundaries between technology and humankind become increasingly blurred.

Work No. 217 ELP I, 1973

By the early 1970s, Giger was a frequent member of the avant-garde art scene and had built a reputation for his stunning, yet divisive, monochromatic paintings. During this time he discovered the airbrush, which gave his art an even harder mechanical edge.

Growing frustrated with the limitations of paper, he also began working in sculpture, wanting to expand his boundaries and make things that existed in 3D.

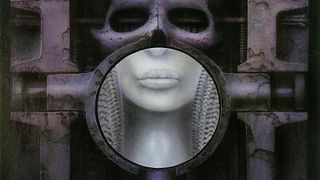

In 1973, Giger was commissioned by progressive rock band Emerson, Lake and Palmer to create the artwork for their new album, Brain Salad Surgery. The final paintings were titled Work No. 217 ELP I and Work No. 218 ELP II, and were created in pure shades of grey airbrush.

This is the first time we really see Giger's beloved biomechanical style, as he creates a cold mechanical interior seemingly imbued with extraterrestrial life. The first painting portrays a mechanism with a human face, the death mask of its skull softened by the tantalising glimpse of a woman's mouth and hair.

Work No. 218 ELP II, 1973

When the album's cover is lifted, the second Giger painting is revealed. It depicts a woman with long hair and multiple scars, including the infinity symbol and what looks like a scar from a frontal lobotomy.

Female faces play an important role in Giger's landscape. They give his paintings a feminine and erotic focus, blending the silky skin and delicate features of a beautiful woman with the relentless drive and limitless power of machinery.

Feminists reportedly hated Giger's art, however, decrying the way women were presented as objects in hypermasculine interiors - as pretty and detached as furniture without any agency of their own.

Despite these criticisms, the paintings for Brain Salad Surgery have become some of Giger's most recognised and loved work. The original acrylic-on-paper paintings were stolen after a Giger exhibition at the National Technical Museum in Prague in 2005, and have never been recovered.

Li I, 1974

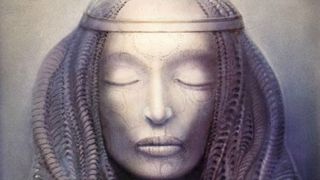

Although female features were frequently weaved into Giger's paintings, there is one woman in particular who appeared in his most famous works. This was Li Tobler, Giger's lover of six years and later his muse.

Giger met the Swiss actress in Zurich in 1966, and the couple enjoyed a mutually artistic and passionate affair. The relationship was rocky, however, punctuated by bouts of promiscuity and drug use.

While this was a fruitful time for Giger, who was experiencing international success, it was a parasitic one for Tobler. As Giger became more well-known and admired, Tobler seemed to fade, suffering from depression and low self-esteem.

In 1974, Giger created two portraits entitled Li I and Li II, in which Tobler looks like a cyberpunk goddess cast in concrete. Once again, life and death are perfectly balanced: Li's skin is as placid and smooth as a doll's, while her hair is braided into a wreath of skulls and serpents.

Instead of feeling flattered, Tobler was allegedly shocked when she saw the pictures. Perhaps they further convinced her that she no identity when she was with Giger; she was just a figment, an extension of his art.

She broke the frame of Li I and tore its fabric. Giger consequently reconstructed it. But not everything could be so easily mended, as Tobler killed herself in 1975.

Li II, 1974

Nevill Drury, who interviewed Giger in 1985 wrote: "Li is the prototype for the many ethereal women in his paintings who peer forth from the torment of snakes, needles and stifling bone prisons – to a world beyond.

"[She was] like a woman of mystery struggling to emerge from the nightmare that has possessed her soul."

Drury concluded his article by saying: "It may be too simplistic to say that Li haunts Giger still, for his life is full of beautiful and exotic women who are fascinated by his art and by his bohemian lifestyle. But there is no doubting that the simultaneous agony and joy of life with Li Tobler established the dynamic of fear and transcendence which is present in many of his paintings."

Mutants, 1975

Some of Giger's works are unnerving because they seem to anticipate a future where technology runs rampant and has developed an independent thought process. This is especially pertinent in the 21st century, with robotics evolving and technology becoming increasingly intelligent.

After witnessing extreme warfare and several advancements in science, Giger feared that as people became more dependent on technology, they would start to lose sight of their own humanity. And if the soul itself becomes mechanised, what does it really mean to be human?

In paintings like Mutants, Giger creates an amalgamated race of alien and machine. The domed craniums and eyeless faces would be recycled in the making of the Alien, while the tubes and sockets are reminiscent of cyborgs.

There have been many warnings shone through art about the growing intelligence of tech and its effects on humanity, but Giger's methods remain some of the most chilling.

Dune concept art, mid 1970s

As the 1970s drew to a close, Giger's work was being exhibited across the world. Thanks to writer Dan O'Bannon, he also came to the attention of Chilean filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky.

The two men were attempting to adapt Frank Hebert's epic sci-fi novel Dune and needed an artist to help bring their vision to life. Sharing Giger's affinity for surrealist storytelling, Jodorowsky enlisted him to produce concept art.

Giger threw himself into the project and completed a number of paintings between 1975 and 1976. These included portraits of a demonic train with a skull-like face and speared tongue, again playing upon Giger's fears of future technology and creating machines with human qualities.

"My planet was ruled by evil," Giger later said of his Dune design, "a place where black magic was practiced, aggressions were let loose, and intemperance and perversion were the order of the day. Just the place for me, in fact."

Dune concept art, mid 1970s

Despite his striking concept art, Hollywood studios were reticent of funding a film with the eccentric Jodorowsky and it never went into production

In 1979, producer Dino de Laurentiis acquired the rights to Dune, seeking Giger as production designer and Ridley Scott as director, before it was shelved once more. It was revived a third time, but the new director, art-house horror aficionado David Lynch, didn't share Jodorowsky's passion for Giger's work and replaced him with his own creative team.

O'Bannon wasn't so easily swayed, however. He later said: "His paintings had a profound effect on me. I had never seen anything that was quite as horrible and at the same time as beautiful as his work."

Spell IV, 1977

In 1977, Giger's third, and most influential, collection was published under the name Necronomicon. The book is a nexus of post-human structures, overt sexuality and demonic shrines. The collection contained more than 200 prints of photographs, paintings, and sculptures, as well as autobiographical text.

The Necronomicon is named after H. P. Lovecraft's fictional grimoire, a dark history about demons and how to summon them.

Paintings like Spell IV (pictured above) bring to mind the freakish characters in Lovecraftian horror, tales in which men struggle against malignant forces, and give viewers a glimpse of Giger's lavishly detailed world of nightmares.

Necronom IV, 1977

It's fascinating to think about what Dune would have been like if Giger and Ridley Scott had worked on it together. Although the project never came to fruition, we did get Alien, a film that re-defined the horror genre and allowed Giger to transform his art into a three-dimensional space.

In 1977, O'Bannon showed a copy of Necronomicon to Scott after his Alien script was given the green light. Scott was fascinated, in particular with the painting Necronom IV, which pictures a cross-breed between man, alien and machine.

Out of all of Giger's creations, the Necronom is perhaps the most terrifying, with its phallic head, exposed ribs, jutting bones and metallic skin. In contrast, the arms and hands appear human, making it all the more queasy to look at.

What makes it worse is the Necronom's undercurrent of eroticism. It's frightening, yes, but also lithe and cat-like, especially in Necronom V, where Giger attaches the head to a curved female body.

This striking combination of horror and sexuality appealed to Scott and what he envisioned for the film. "It could just as easily fuck you before it killed you," said Alien line producer Ivor Powell, "[making] it all the more disconcerting."

Initially, Giger wanted to design the creature from scratch, but Scott was so transfixed with the Necronom pictures, he insisted Giger follow their form.

It didn't appeal to everyone. Scott's producer, Gordon Carroll, was visibly repulsed, and called Giger's artwork "sick", but Scott would rebuke him, later saying, "I've never been so certain about anything in my life."

Xenomorph concept art, 1978

Fox Studios initially thought Giger's artwork was too disturbing, but they eventually relented and Giger was flown to England to start working on Alien.

While there, Giger worked in a custom workspace at Shepperton Studios where he created the full-size Alien sculpture, in addition to the face hugger and chestburster models. He also constructed the derelict spaceship, the space jockey and egg chamber, and airbrushed the entire set by hand.

Alien is so effective because it preys on the fears of childhood. It tells us that there is something lurking in the shadows, and that it's coming for us. The heroine of the film, Ellen Ripley, becomes Little Red Riding Hood in a post-industrial wasteland, while the Xenomorph looks like it's been plucked from a nightmare realm of Freudian symbolism and subconscious terrors.

The Xenomorph is also disturbing because we can never really figure out what it's made of. In some scenes it looks robotic, sinking against the Nostromo's walls like a steel structure covered in black scales. At other times it looks sickeningly organic, its multiple jaws dripping fluid wherever it goes.

The design of the Xenomorph and the tense, suffocating atmosphere makes Alien the best film in the series. Scott's Nostromo is a maze of hallways and rooms, bathing in shifting coils of shadow and silently ensnaring each member of the crew in the Xenomorph's sticky web.

Giger's work earned him the 1980 Oscar for the Best Achievement in Visual Effects for his designs of the film's title character, including all the stages of its lifecycle, and the extra-terrestrial environments.

See more pictures of Giger's Xenomorph here.

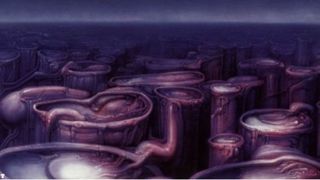

LV-426 landscapes, 1978

As previously mentioned, Giger also created several landscape paintings of planetoid LV-426, where the crew of the Nostromo encounter the derelict spacecraft. These lush plains are as gorgeous as they are nauseating, and are some of the only times Giger abandoned his monochrome airbrush.

Swathed in palates of midnight purple, rosy pink and powder blue, Giger's landscapes look alive, throbbing like blood vessels across the surface of the alien moon. Tubes and tendons, pockets of pus; you can imaging the ground undulating beneath your feet and the hot, humid air against your face.

Although the moon wasn't depicted in this way, Giger's opulent style of world building is breathtaking, and it's refreshing to see softer works from an artist usually described as cold and mechanical.

Facehuggers, 1978

Here we can see Alien's infamous facehuggers: a revolting hybrid of squid and spider, and a process that grossly exaggerates phobias of being smothered and swallowing insects in our sleep.

Derelict spaceship, 1978

This is one of the pictures of the derelict spaceship on planetoid LV-426. The resemblance between Giger's pictures and what was replicated in the film is uncanny, as if the cast had fallen into Giger's artwork.

Space Jockey, 1978

One of the most recognisable images from Alien is of the space jockey, a nickname given to the pilot of the spaceship found on LV-426. Again, this was a concept of Giger's that translated perfectly to Scott's film.

KooKoo, 1981

After the frenzied success of Alien and sharing the red carpet with Hollywood's elite, Giger discovered he had become a household name. With mainstream success came a glamorous new audience and in 1981, Debbie Harry asked Giger to design the cover art for her first solo album, KooKoo.

Compared to Giger's previous artwork, the cover looks softcore, and would be unremarkable if it wasn't for the stormy shades and the giant needles piercing Harry's cheek. Apparently Harry was taken aback by the cover, and was reticent about using it. It's a good thing she did because it's the edgiest she's ever looked, and helped fortify her new image as a strong solo musician.

Species concept art, 1994

Unfortunately Giger never reclaimed the level of success that came with Alien. He worked on a number of films in the 1980s and early 90s, such as Poltergeist II, Future Kill and Alien 3, but they were frustrating experiences for an artist used to creative freedom and the films opened to lukewarm reactions.

In the early 90s, Giger was invited to work on a sci-fi film called Species, about an alien seductress that must be hunted down before she can mate with a human male. Giger seized the chance and was delighted to design what he called "an aesthetic warrior, also sensual and deadly, like the women look in my paintings."

Although the final film deviated greatly from Giger's plans of an alien with transparent skin and a black interior, "like a glass body but with carbon inside", the concept art is Giger at his finest - elegant, sinister, titillating.

Most Popular