There's a Far Side cartoon by Gary Larson that shows two doting parents watching their son playing a console while they dream about newspapers full of job adverts stating 'Nintendo expert needed'.

A ludicrous notion perhaps, but for some people, making money from their videogame hobby has become a reality – although not in the way Larson may have expected.

They do it by making music. This is the chiptune scene, a fantastical future where music is made using the sound chips from the past. Old computers like the BBC Micro or games consoles such as the Nintendo Game Boy and Commodore 64 become instruments, their dated hardware exuding a delicious modern charm.

A lot of people have described chiptune as being a genre, but strictly speaking, that's a bit like describing a keyboard as a genre, as chiptune artist PixelH8, also known as Matthew Applegate, is quick to point out.

"Chiptune describes the instrumentation," he explains. "Sonically, it sounds very similar to videogame music, but it's not accompaniment. It's music in its own right."

Risking death

PixelH8 has been described as the godfather of the UK chiptune music scene, with three albums under his belt. His music has led him to work with artists as diverse as Imogen Heap and Damon Albarn. So how did he get started?

Get the best Black Friday deals direct to your inbox, plus news, reviews, and more.

Sign up to be the first to know about unmissable Black Friday deals on top tech, plus get all your favorite TechRadar content.

"It was an accident, a wonderful accident. My baby sister, who was about one at the time, sneaked into my bedroom and poured her bottle of milk into my Nintendo. It was a combination of my being 11 and foolish. I had a screwdriver and I thought I could fix it.

"In hindsight, it was very dangerous and I didn't know what I was doing. But what I did discover was that if I stuck the screwdriver in different places at different times, I could short-circuit it, making it make crazy noises."

Five years later, he was properly making chiptune music using an Amiga 500: "I was in a bad REM cover band and I was using the Amiga 500 for the orchestral backing. It only made simplistic beeps but I fell in love with it. But then, when the modern PC came into my home, I used it to learn about older machines instead of using it for synthesis."

Applegate says the biggest challenge for chiptune artists is getting the right sound from these old machines. "I'm such a perfectionist when it comes to capturing sounds," he says. "I spend hours recording sounds again and again. Even the most basic sound can take ages. I think the real challenge in chiptune music is just to be happy with what you've created."

The older the better

PixelH8 has a close relationship with the National Museum of Computing, located at Bletchley Park, which contains some of the earliest examples of computers. They've let him get his hands on some of their exhibits.

What's the oldest machine he's used in his music? "I think it was the Elliott 803 [from 1961], a wonderful machine being kept in good working order by a man called Peter Onion. Although I did use the Colossus, it was a rebuild and not the original from the 1940s.

"The Elliott 803, from what I could deduce, makes around two octaves of F major, and can't produce some of those notes 100 per cent – but that's what's great about it. It wasn't a music machine. The sounds are largely a by-product of the machines working, but in my work, that aspect is brought to the forefront."

Applegate loves where chiptune music has taken him. "I've been able to travel and meet interesting people; my music has taken me to places I never thought I would go or be capable of going. I have been very fortunate to meet a lot of talented musicians. The work I usually do is advisory or to make a little bit of software to make a certain chiptune sound, and it all seems to have a knock-on effect. I do one thing for someone and they recommend me to someone else and so on.

"Imogen Heap was the first lady to really like what I did. She ran a competition on MySpace for an opening act and I posted a YouTube link on her page of me circuit-bending a toy keyboard. She invited me to Brighton and the rest is history."

New blood

Unsurprisingly, there are others keen to tread a similar path in the world of chiptune music. Someone just starting out is The Disco King, or Adam Lee to his friends, and he's already played at Glastonbury, albeit in the Shangri-La area.

We asked him how he got bitten by the chiptune music bug. "I've been making music and playing games for years," he explains, "but I discovered the chiptune scene back in uni. It's partly the nostalgia factor, but I also just love the simplicity of those sounds. One of my favourite things is hearing a Commodore 64 bassline through a huge speaker setup in a club. You'd be really surprised at just how good it sounds!"

You can hear The Disco King's 8-bit cover of Kansas's Carry On Wayward Son, and how it was created, on our sister publication MusicRadar.

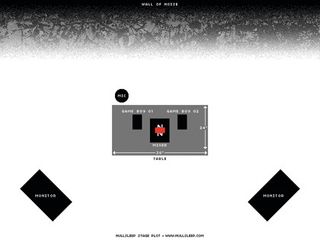

Lee is supported in his ambitions by people such as Laurie French, who helped him set up the Glastonbury gig as part of 8-bit event Micro Rave, a night that usually finds its home in Bristol. French explains that the aim of Micro Rave is "to plunge the public into the heart of an old computer game, complete with badly drawn graphics, pixellated cardboard-based baddies and cheap plot-lines, but most of all? Fat 8-bit music at loud volumes!"

So what does it involve? "The night usually consists of lots of crazy dance-off type battles and games to determine who has what it takes to tackle the main challenges. Then, as the narrative unfolds, the games usually culminate in several selected rebel guardians being dressed as warriors and defending the headline act from abduction by invading robots, by using oversized foam powerhammers. Then when the planet has been saved from evil, much celebration ensues as the headline act plays!"

It's not for everybody, perhaps, but there's no doubt that it's appropriate to the genre.

Most Popular