From parts to product: how a Windows 10 device is born

The Pyramid Flipper developers tell all

Building a Windows 10 device, especially a tablet, isn't a straightforward task. If it were easy, everyone would be doing it. But while your next-door neighbor isn't making the next Surface Pro, "the 24 man team who want to change the world" at startup Eve-Tech can tell you just how laborious a process it's been to devise their crowd-sourced Pyramid Flipper 2-in-1 tablet.

Techradar spoke with Eve-Tech CEO Konstantinos Karatsevidis to get the inside scoop of how a Microsoft-licensed device goes from an inkling to a final product delivered at your doorstep.

Pleasing everyone

Eve-Tech, Kaatsevidis tells us it all started two years ago, from his home in Finland, alongside his co-founder Mike. The pair were discussing the latest flagship tech devices on the horizon

Unfortunately, having already purchased a number of flagship devices, one thing the two noticed was how "terribly overpriced" and "poorly designed" they were. For their expensive cost of entry, the performance was all but impressive.

In turn, this led to the development of the Eve T1 Windows tablet in 2013, and more importantly, the creation of the Eve-Tech label itself.

"It was actually a quite nice device," Karatsevidis said. "It was basically our first attempt almost on our own. There were a couple more people we used, but we all sourced everything, and it got plenty of press coverage."

At 159 Euros (about $171, £118, AU$233), the T1 was much more affordable than other competing devices on the market at the time, but it wasn't enough for most consumers.

Get the best Black Friday deals direct to your inbox, plus news, reviews, and more.

Sign up to be the first to know about unmissable Black Friday deals on top tech, plus get all your favorite TechRadar content.

"There were always people saying what they would do to improve the device," Karatsevidis recalls. "They were asking why nobody has this type of screen in the product. So like, 'yeah, it's an amazingly priced device, but wouldn't it be great if it had this and that?'"

As a result, Karatsevidis and company took it upon themselves to make a Windows 10 device that appeals to everyone, building a community around "people who typically argue in the comments sections," where they can all come together and reach a consensus on what makes for a perfect device.

Designing the perfect device

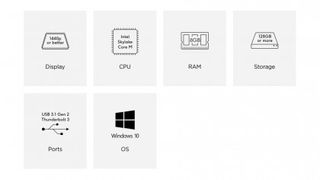

In building hardware, the first step is locking down the desired specifications alongside a meticulous industrial and mechanical design process.

As for determining the specs, Karatsevidis describes a highly unusual process of asking the community what they want in a 2-in-1, issuing polls asking a wide range of questions, from what they would like to see for a CPU to what kind of glass they should use on the display.

The most popularly sought out features, he tells us, were a 24-hour battery life, 8GB of RAM combined with "a powerful processor," Thunderbolt 3, a kickstand, and a "good, more personal design," whatever that means.

The industrial design wasn't crowd-sourced, and instead was completed in conjunction with the company's Swedish partners.

Consequently, the industrial designers take their concepts to the mechanical designers, which, as Karatsevidis tells me, lead to frequent feuds between the two parties.

While the industrial designers had their hearts set on a sleek and aesthetically pleasing piece of hardware, mechanical engineers are more focused on the realities of manufacturing.

Going shopping

After settling on a design is when the manufacturer moves on to sourcing an extensive list of components from a manufacturing partner.

In the Pyramid Flipper's case, this means around 2,000 parts. That's a lot of moving parts, and the hardest thing to crack is where all of these puzzle pieces come from.

"Let's say that out of these 2,000 components, 900 components are really easy to find, but then around 10 or 15 components are really tough to get,," Karatsevidis explained. "Basically, that is where our team has been working [for] much more than just two weeks, we started almost half a year before that."

"Go to the store and get any components you want to get. In reality it's the complete opposite."

"Most people, they think that building a great tablet or smartphone is the same as building a great performance PC," he says. "You just go to the store and get any components you want to get. In reality it's the complete opposite."

Unlike going on Newegg and prepping your own beastly rig, no one wants to sell components to a tablet manufacturer en masse. They have to make sure there's an economic return already secured, and for startups this can be a strenuous task.

Rather than paying for everything upfront, which would be next to impossible for anyone running a smart business, the manufacturer has to convince the parts sellers that they're worth considering as partners. Failing to accomplish this, because of the current state of the components industry, could lead a company to start clutching at straws.

"This components industry," Karatsevidis said, "I would say it's actually quite monopolized in some sense. For example, [for] LCD suppliers, there are only five big ones in the world. And, out of those five, there are only two -- Samsung and LG – that provide high quality screens for tablets and laptops."

With companies as large as Samsung and LG running the whole game, it's not easy to get their approval without the promise of pushing millions and millions of devices out the door come release time. As Karatsevidis puts it, "It's really hard if you're below half a million devices a year to get the 80 components you want."

Luckily, thanks to a unique crowdsourcing model, Eve-Tech was able to meet with both Samsung and LG to get exactly the screen the community asked for. Giving companies the proof of demand assuredly allowed the company to finalize the deal.

Unfortunately, the Eve-Tech showrunner informed us that this was a rarity among PC and tablet makers.

"Typically that's something that almost never happens, even with the appropriate credentials," he says.

Most Popular